New Timelines for Inhabitants of Denisova Cave

Denisova Cave in central Asia is becoming quite the celebrity residence – at least in the fields of archaeology and hominin research. It must have been an extremely attractive home for Homo sapiens and other hominin species because it is the only place in the world where we know that all three species resided at one time or another: Humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans. We can guess why: It was a warm space, securely located up a hillside slope. It had a large floor plan, about 2,900 square feet, high ceilings, and a great view! From their vantage point, inhabitants would have been able to spot prey as they approached the Anui River in the valley below.

View from Denisova Cave hillside (Source: Nature)

Denisova Cave first caught the world’s attention in 2010 when the DNA from a finger bone there proved to belong to a hitherto unknown species of hominin – now called the Denisovans. A Neanderthal bone was found the same year and since then six individuals have been identified: 4 Denisovans, 1 Neanderthal, and one hybrid.

Two new papers published in the journal Nature provide updated data about when habitation may have occurred at Denisova Cave. One of the studies focused on dating the fossils[1]Katerina Douka, Viviane Slon, Zenobia Jacobs, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Michael V. Shunkov, Anatoly P. Derevianko, Fabrizio Mafessoni, Maxim B. Kozlikin, Bo Li, Rainer Grün, Daniel Comeskey, Thibaut … Continue reading while the other dated the sediment next to tools and artifacts discovered in the various layers of soil.[2]Zenobia Jacobs, Bo Li, Michael V. Shunkov, Maxim B. Kozlikin, Nataliya S. Bolikhovskaya, Alexander K. Agadjanian, Vladimir A. Uliyanov, Sergei K. Vasiliev, Kieran O’Gorman, Anatoly P. … Continue reading

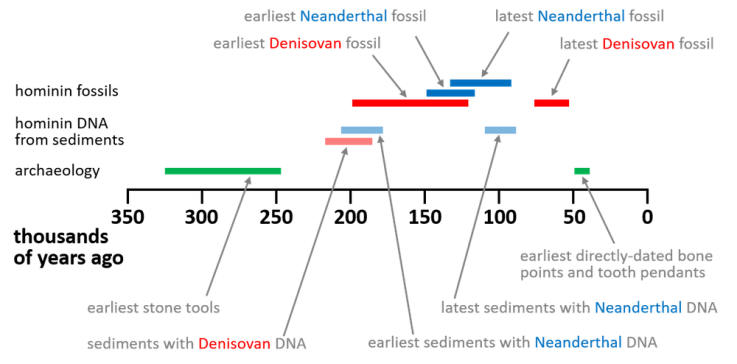

According to the dating techniques employed, hominids have likely inhabited the cave for at least 300,000 years. It is unclear which hominid was residing there the first 100,000 years or more, but there is evidence of Denisovans in the cave from about 200,000 years ago (ya) to as recently as 52,000 ya, with possible breaks in-between. Neanderthal presence apparently overlaps Denisovan presence. Neanderthals are estimated to have been in the cave from approximately 200,000 to 80,000 ya, again with breaks in-between. It is unknown if the two species co-inhabited the cave or fought for ownership. We know there was interbreeding, regardless. “Denny,” the hybrid daughter of a Denisovan father and Neanderthal mother, was present in the cave about 90,000 ya. (See my blog post about Denny here.)

Habitation Timeline for Denisova Cave based upon two January 2019 studies. (Source: Prof. Richard Roberts)

In addition, there is some suggestion that the Neanderthal presence may have occurred when the climate was warmer and the Denisovan presence when the climate was colder. The strongest evidence for Neanderthal presence occurs around 120,000 ya during a major interglacial period.

Homo sapiens probably arrived after 50,000 ya, although no human bones have been found for this Upper Paleolithic period. There are some bone points and tooth pendants from the cave dated to between 49,000 and 43,000 ya, the ownership of which are in question. One of the research teams thinks it’s possible the artifacts were made by Denisovans, but Professor Chris Stringer of London’s Natural History Museum believes they likely belonged to early modern humans.[3]Laura Geggel, “Neanderthals and Denisovans Lived (and Mated) in this Siberian Cave,” LiveScience.com, 31 January 2019; published here. It could well be that a branch of the big H. sapiens migration out of Africa circa 60,000 ya made its way to Denisova Cave and pushed the Denisovans out. The timing makes sense because we humans had made our way to other parts of Asia around the same time – certainly by 45,000 ya.

The authors caution that all the dates are approximate especially those older than 50,000 ya. Nonetheless, it gives us a rough idea of who may have lived in Denisova Cave and when. Digging continues.

Although this is speculative, my theory is that Denisovans occupied the cave initially. We know Denisovans are an offshoot of Neanderthals. They split about 400,000 ya, so we can imagine that the original Denisovan population moved east from the Neanderthal heartland in Europe and occupied Denisova Cave sometime between 350,000 to 300,000 ya. and remained there either continously or episodically for many millenia. Neanderthals are known to have expanded their range east into Asia during the Eemain Interglacial Period, which began about 130,000 ya. So my guess is that in moving east, Neanderthals took over Denisova Cave around 130,000 ya and occupied it until 80,000 ya or so. The hybridization event at 90,000 ya could be a by-product of Denisovans reasserting control of the cave or represent incidental contact between Neanderthals in the cave and Denisovans in the surrounding area. Denisovans then occupied the cave until humans came along around 50,000 ya and pushed them out.

I noticed on TripAdvisor.com that a handful of hardy tourists have actually made their way to Denisova Cave, despite its distance from airports and the fact that you have to drive many bumpy hours to find it. The ones who made it there raved about the experience though!

References

| ↑1 | Katerina Douka, Viviane Slon, Zenobia Jacobs, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Michael V. Shunkov, Anatoly P. Derevianko, Fabrizio Mafessoni, Maxim B. Kozlikin, Bo Li, Rainer Grün, Daniel Comeskey, Thibaut Devièse, Samantha Brown, Bence Viola, Leslie Kinsley, Michael Buckley, Matthias Meyer, Richard G. Roberts, Svante Pääbo, Janet Kelso & Tom Higham, “Age estimates for hominin fossils and the onset of the Upper Palaeolithic at Denisova Cave,” Nature volume 565, pages 640–644 (2019); Published: 30 January 2019. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Zenobia Jacobs, Bo Li, Michael V. Shunkov, Maxim B. Kozlikin, Nataliya S. Bolikhovskaya, Alexander K. Agadjanian, Vladimir A. Uliyanov, Sergei K. Vasiliev, Kieran O’Gorman, Anatoly P. Derevianko & Richard G. Roberts, “Timing of archaic hominin occupation of Denisova Cave in southern Siberia,” Nature volume 565, pages 594–599 (2019); Published: |

| ↑3 | Laura Geggel, “Neanderthals and Denisovans Lived (and Mated) in this Siberian Cave,” LiveScience.com, 31 January 2019; published here. |